Metrics. KPIs. ROI.

Metrics. KPIs. ROI.

Oh, the humanity!

Gini Dietrich asked me to blog on measuring public relations.

So, naturally I chose to blog on PR stunts.

Same thing, right?

Blame my anti-authoritarian nature.

Besides, who wants to talk numbers and measurements with the holidays right around the corner?

Now when I refer to PR stunts, I am not talking viral videos here or millions of people creating a chain by holding hands.

Those are not what I consider true PR stunts.

I am a student of history.

My Top Three PR Stunts (All Prior to 1926)

I appreciate things that get better with time: Beef, scotch, my 401k, and PR stunts.

So, all you Tweeters might be disappointed to learn the PR stunts I admire are not likely the ones you prefer.

My favorites took place in the good ol’ days.

These stunts were gritty; they were gutsy.

They could never be pulled off today.

And I have no time or interest in measuring their results, perceived or actual.

These were simply self-standing episodes of ingenuity.

Besides, as a firm believer in AVEs, you wouldn’t want me measuring things.

The 1773 Boston Tea Party

Yes, you lager lovers, John Adams pulled off what I consider to be the greatest PR stunt ever, a mere 125 plus years before America’s first publicity office was even opened for business.

To protest the Sugar Act and Stamp Act in the mid-1760s, Adams unified and organized Bostonians into a group who became known as the Sons of Liberty.

Adams masterminded attacks that served to bully tax collectors.

These tactics were indeed violent.

They included arson, destruction of buildings, and the burning of British effigies from the Liberty Tree.

Adams understood the power of a motivated and passionate populace, which stoked through the activities of the Sons of Liberty.

Organizing, fanning the flames, intimidation—those are all fine and dandy, but minor compared to his master stroke, his PR coup, his beautiful PR stunt, his legacy: The organization of the December 16, 1773 Boston Tea Party.

This event could be said to be one of the germinal event that precipitated the Revolutionary War.

Now that’s a return-on-investment.

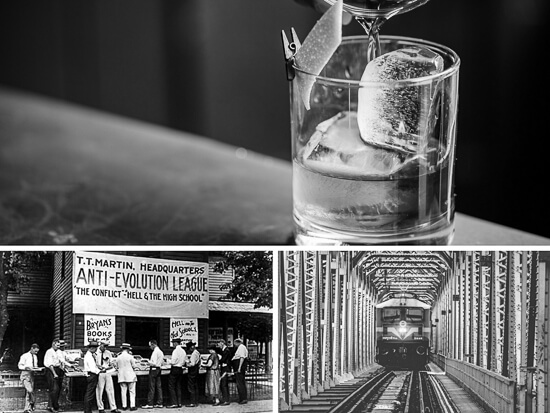

The 1896 Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad Train Crash

William George Crush.

Could you think of a better name for the mastermind of a planned train crash? (OK, I hear you, maybe Crash?)

Oh to have witnessed this delightfully grimy sensory feast.

As if the entire 19th century wasn’t gritty enough, Mr. Crush comes along and wants to see a couple of trains fly headlong into one another.

A simple passenger agent for the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad, Crush got the OK from his superiors to crash.

He worked to advertise the event throughout the preceding summer with circulars and bulletins.

His efforts were rewarded by 40,000 attendees.

At exactly 5:00 p.m., September 15, 1896, the trains at opposite ends of a several-mile track were prepared to take off.

And our simple passenger agent?

He galloped in atop a white steed and faced the spectators.

A white steed!

From his saddle, he signaled the engines to get moving by waving his what else? His white hat.

I have goosebumps.

Upon collision, the forward motions of the engines pushed both engines skyward.

BOOM. Steel bent and screamed.

Now there was a terrible downside.

The boilers unexpectedly exploded (Hello engineers? Unexpectedly exploded?), and unfortunately, this PR stunt was the last thing three observers ever witnesses.

Nonetheless, the crash worked.

Why?

Because the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad was the talk of Texas.

People clamored to ride the line gutsy enough to pull off a massive train wreck.

How much did it work?

How many people wanted to ride the train afterwards, Gini?

I have no idea.

The 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial

Inherit the Wind. A genuinely fine play.

Anyone?

Have they pulled this work from the high school curriculum also?

Dayton, Tennessee. Ever hear of it?

Well that may be why they were looking for a little attention, a little publicity.

How about a PR stunt?

On March 13, 1925, the Sixty-Fourth General Assembly of the State of Tennessee passed the Evolution Statutes.

An Act prohibiting the teaching of the Evolution Theory…

…it shall be unlawful for any teacher… [receiving] funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible…

any teacher found guilty of the violation of this Act, Shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction…

Folks in Dayton thought that national publicity would roll in if they could simply locate an evolution-teaching instructor.

They found a teacher who would help them, a guy named John Scopes.

He agreed to read a bit about evolution to a class and was quickly arrested.

Indeed the instructor was innocent until proven guilty.

To determine guilt, there needed to be a trial.

And that trial would take place in Dayton.

Once the staged trial started, the interest was far-reaching.

One of the reasons for the publicity was the case pitted two celebrity lawyers against one another: William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow.

Dayton found its publicity.

It became nationally known as “Monkey Town.”

New business sprang up to address the needs of a flood of tourists.

How much investment was generated for Dayton? Was it long lasting?

I don’t know.

Who won the trial?

Who cares.

It was simply a gutsy PR stunt.

image credit: Flickr/Mike Licht