Elon Musk is a very smart man.

Elon Musk is a very smart man.

After all, he co-founded PayPal and then took that money and founded SpaceX (a company designed to get man on Mars, where he wants to die) and co-founded Tesla Motors (a company designed to make really fast, really awesome, really beautiful, really expensive electric cars).

He’s enjoyed a pretty admirable reputation. Everything he touches seems to turn to gold. Heck, he’s only a few years older than me and he’s a self-made gazillionnaire (jerk). But I have one thing he doesn’t have: Communication skills.

Enter the New York Times

Last month, New York Times reporter John Broder took the electric Tesla Model S Sedan for a test drive along the newly electrified stretch of I-95 on the east coast. The electric-car manufacturer helped put charging points into place at service stations at 200 mile intervals along the freeway.

Broder wrote in his review about the car, “That is well within the Model S’s 265-mile estimated range, as rated by the Environmental Protection Agency, for the version with an 85 kilowatt-hour battery that I drove – and even more comfortably within Tesla’s claim of 300 miles of range under idea conditions. Of course, mileage my vary.”

So far, so good. Broder has the information he needs from Tesla. The company’s messaging is accurate, the charging stations are close enough together, and he’s ready to take his drive. He goes on to compliment how gorgeous the car is and how much he likes the Google-driven navigation system. He talks about all of the awards the car has won and how much fun he expects it will be to drive. All of this, of course, based on what the car company has told him.

And then he experiences the car himself. He starts off on a nice drive on a 30 degree day and makes it to the first charging station just fine. And then the proverbial wheels come off. While the car’s system said it was fully charged, Broder discovers he’s losing charged miles faster than he should so he slows down, turns off the heat, and drives in the right lane until he can get to the next charging station. Frustrated, he charges it and gets to a hotel with some 90 miles left of range, about twice the 46 miles he needs to get back to a charging station the next morning.

But when he gets up and goes out to start the car in the now 10 degree weather, he finds the car display shows only 25 miles of remaining range and he won’t be able to make it to the charging station. By the end, he has to have the car towed to the charging station where he waited 80 minutes for it to recharge so he could get back to Manhattan.

This recap is retold in an eloquent 2,000 word article that details every moment of the more than 24 hour test drive. Broder describes how several different Tesla employees helped him – everyone from an agent and product planner to the chief technology officer – during his drive.

Defensive vs. Factual

And then Elon Musk gets involved.

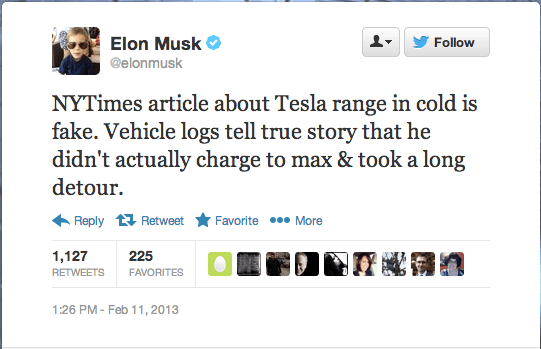

Three days after Broder’s article runs, Musk tweets, “NYTimes article about Tesla range in cold is fake. Vehicle logs tell story that he didn’t actually charge to max & took a long detour.”

Even if he didn’t charge to the maximum and he did take a long detour, as both a Tesla customer and a highly-influential journalist, his experience is different than what the company promised.

Imagine if Broder had just paid more than $100,000 for the car and had this experience. Let’s say he then tweets about it and puts it on Facebook and tells his friends not to buy it. Would Musk debate him then?

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end there. Musk continues to tell the world why Broder is wrong, detailing their side of the story on the Tesla blog. Some rabid Tesla fans have come to Musk’s defense, but overall, he looks defensive.

The Risk of DIY Earned Media

This demonstrates both the magic and the challenge of earned media. If your customers and influencers love what you’re selling and have the same experience as you’ve told them to expect, earned media and social media both work magically in your favor. It’s good for your ego, it’s good for business, and it makes people want to buy from you.

But if, operationally, things are not what they seem and a customer has an experience very different than what you tell them to expect, they now have a very large voice.

It used to be, if a story like this ran, the communications professionals would be brought in. First we’d be admonished for “letting this happen” and then we’d be told to fix it.

We’d call the journalist and work very hard to get either a second story or a retraction. The latter, of course, nearly impossible in this particular scenario.

But now? Now everyone has a voice, including the leader of an organization who isn’t accustomed to being told he’s wrong. He’s acting on emotion, not on strategy or planning. He’s acting without the benefit of a consulting his communication professionals.

And acting on emotion, no matter how smart you are, always gets you in trouble. Always.