By now you’ve probably heard about Anthony Weiner’s communications director going off the rails.

I’m not going to repeat here what she said, but let’s just say she called a former intern some really awful names. And, if that weren’t enough, she did so while talking with a journalist.

The story goes like this: A former intern wrote an article for the New York Daily News about the inner workings of the Weiner campaign. In it, she described how most interns work for Weiner simply to get to know his wife (whose boss is Hillary Clinton) in hopes of making it on to the 2016 Presidential campaign, should Clinton run.

She goes on to describe the “short resumes” of many of the staff members, including communications director Barbara Morgan. Talking Points Memo called Morgan to discuss the Daily News article and that’s when she went on a profanity-laced tirade against the intern, calling her every name in the book and some made up ones, too.

When Jill Colvin, the senior political reporter at the New York Observer called Morgan to find out why she reacted the way she did, Morgan said, “I thought it was an off-the-record conversation.”

You can read about it on Gawker by clicking here.

No Such Thing as Off-the-Record

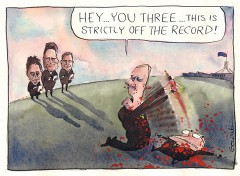

Here’s where I have a problem: You are the communications director. I don’t care if your resume is short. You, of all people, should know there is no such thing as an off-the-record conversation.

Even if you have a verbal agreement from a journalist that they won’t print what you’ve said (and I’ve never met a journalist who will agree to that), they can always print what you said as an anonymous informant or pieces of what you said – maybe unwittingly so – can very easily come through in other pieces he or she will write.

When we do media training for clients, this is the one thing we drill into their heads over and over and over again. There is no such thing as off-the-record.

Here’s the problem: As soon as you lean in and say to a journalist, “I’m going to tell you something, but it’s off-the record,” they know you’re about to give them something really juicy.

The unethical ones will keep silent or grin slightly as if to say, “Okay, we have a deal” so you’ll spill the beans. The ethical ones will tell you nothing is off-the-record, but cross all their fingers and toes in hopes you’ll still tell them what you have to say.

Think about it from your own perspective. If you have a friend who says, “I have to tell you something, but you can’t tell anyone,” what is the very first thing you want to do? It’s freaking human nature. We want to tell the whole world. Of course, some of us don’t, but that urge is really hard to fight.

A Former Client Experience

Early in my career, I worked on The Catfish Institute account. In fact, that account was a huge coup for me in my career because their president at the time is a lifelong friend of mine and I am the one who secured the multi-year, multi-million dollar business for the agency.

So, of course, I had carte blanche in dealings with the clients, including sitting in extremely high-level strategy sessions that I, at all of 26 years old, had no business being in.

About a year into working with them, I gained a valuable experience.

An Asian country was dumping catfish into the United States and calling it U.S. farm-raised. It was a really big deal and it required senior-level expertise from our office, the headquarters office in St. Louis, and the Washington, D.C. office.

I received a year-long education in lobbying and regulatory affairs while we worked hard to get the government to put a stop to this.

During the process, “60 Minutes” – which was to be the pinnacle of my career – wanted to do a story about catfish farming, how to prepare the flaky white fish, and what farmers were doing about the bottom-dwelling, bottom-feeding creatures to make them more appealing to Americans.

We called in the big guns for this one. I can’t remember how much it cost for three days of media training, but I’d venture to guess it was more than $50,000. During those three days, we prepared the president and the chairman of the board for every possible question.

We had one missive: Don’t talk about the catfish dumping.

You see, we weren’t prepared to discuss it and it was still very highly confidential, even though we were working hard in Washington.

The interview went spectacularly well. The TV crews, producers, and on-camera talent spent a few days in Mississippi. They talked to catfish farmers. They fed the catfish. They ate the catfish. They lived and breathed the catfish.

The interview was over and we were about 15 minutes away from celebrating. We were in The Catfish Farmer offices and the chairman of the board and the president walked the producer and one of the cameramen to the front door.

To this day, I don’t know which one of them said it, but the words, “We’re so glad you didn’t ask us about the Asians dumping catfish into the U.S.” came out of someone’s mouth.

The cameras were packed up. The microphones were put away. The on-camera talent was safely tucked in the car to go back to the airport.

Guess what the story was about?

Three glorious days of filming a story with incredible interviews, beauty shots, and even catfish that cooperated. And the story ended up being about the Asian country that was dumping catfish into the United States.

There is no such thing as off-the-record.