Last week, I mentioned that I’ve done more crisis communications work in the past six months than I have in probably the last two years combined.

Last week, I mentioned that I’ve done more crisis communications work in the past six months than I have in probably the last two years combined.

It turns out that a crisis for pretty much every organization is not “if” but “when.”

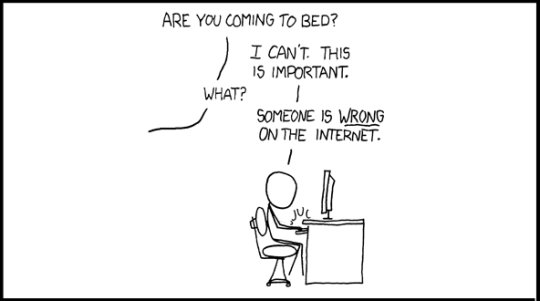

To boot, we have keyboard warriors who sit behind their computer screens and play armchair quarterback without a single ounce of understanding as to what’s really happening.

Woo-wee! I’ve seen some doozies and it’s really challenging to not respond with, “I’ll tell you what—you sit in the (virtual) war room for half a day and see if you make it. If you do, then you can comment on all of this.”

Of course I can’t say that—and it wouldn’t work if I did. It’s really more about proving someone on the internet is wrong than actually being responsible.

But it sure would be nice to sit behind MY computer screen and prove them all wrong.

Alas.

As we think about the “when” this happens to us scenario, it’s important to understand the difference between an issue and a crisis.

If it’s just an issue, you probably can deal with it in the eye of the storm (though not really recommended).

So what is the difference?

An Issue vs. a Crisis

You want to refer back to this list often.

In fact, I’d go ahead and jot it down on a post-it note.

Stick it to your computer, where you can see it every day.

That way, when you’re in the thick of things, you’ll know where you stand—and if you need to quickly bring in professional help.

An issue:

- Is not harmful to an organization’s reputation;

- Does not affect the bottom line;

- Can almost always be avoided;

- Can escalate into a crisis, if not handled immediately; and

- Is a blip in the 24/7 news cycle.

A crisis, on the other hand:

- Has long-term repercussion on an organization’s reputation;

- Generates a loss of money…generally lots of it; and

- Can always be avoided.

Most of us face issues every day…they are things that can be avoided and can be managed fairly efficiently and easily.

When they escalate into crises, though, is when we let the events get the better of us.

Define Your Crisis Communications Plan

When an issue becomes a crisis, one of two things can happen:

- You can pay a gazillion dollars to have professional help because you were not ready; or

- You can have a crisis communications plan ready to go.

Here are six things to include in your crisis communications planning:

- What’s the worst thing that could happen? This is where you brainstorm every possible worst case scenario that could happen to your organization. This should capture everything from marketing campaigns that go off the rails (like Qanon claiming your undergarments are tracking people), to natural disasters and terrorist attacks. Not all crisis has an external source either. Prepare for things your executive team could do. These might include a poorly thought-out social media posts, sexual harassment, or tax evasion. Include employees at varying levels from departments across your organization.

- Is this scenario an issue or a crisis? An issue is a kerfuffle—it isn’t going to do damage to your company’s reputation or your bottom line. But, if you don’t deal with it quickly, it could morph into a crisis. A crisis, in comparison, negatively affects your company’s reputation and results in a significant loss of revenue. The president tweeting to ban your product, while painful, is an issue. Your product containing salmonella and making a bunch of people sick is a crisis.

- How big is our risk? Not all crises demand all-hands-on-deck and sleeping in the office until they are resolved. Rank your scenarios on a scale of one to five, with a one being low risk (but still important) and a five involving setting up sleeping bags in the boardroom.

- Can it be prevented? You can’t prevent every unhappy customer or predict manufacturing issues that can cause a need for product recalls, but there are some things you can at least work towards preventing (such as an ill-conceived marketing campaign) through better due diligence or more thorough planning and training.

- What would escalate a crisis? Sometimes a crisis may start off as a three, but rapidly escalate. What are factors that could cause an escalation?

- Who needs to know and when? Although some people like to call a news conference whenever a thought enters their heads, not all crises merit a public mass communication. If you receive a negative review on an industry review site, for instance, you should make your sales and customer service teams aware of it, and provide some talking points, but you don’t need to issue a news release refuting it point-by-point (over-defensive much?). But if an executive is leaving the company to head up a rival firm, pretty much everyone needs to know, ASAP, starting with your employees, board members, and investors. Failure to get out in front of a story like this is a great example of how a crisis escalates.

While a crisis communications plan won’t be able to account for everything that could happen, the process of planning will.

Defining how you will respond, and who will be involved in which activities, goes a long way to helping you keep a cool head and react thoughtfully when the unexpected arises.